It happened in November 2018, in the perfect breezy pre-winter weather of Hemonto. We went to attend a Chakma friend’s wedding in Rangamati, and got lucky to catch a glimpse of the annual Buddhist festival of Kothin Chibor Daan.

We were beaming in enthusiasm to write about it, the magic still spellbound us after we were back in Dhaka, and Sarah-Jane decided to write about it. The whole memory of it was like a jingle of poetry in our head, and she quickly started writing it as if it was a travel blog written as a poem. She could not finish it. We could not finish it.

Until recently, six years later, on another November weekend of Hemonto in 2024, I decided to write. Of course, I could not continue it as a poem, and turned it into a crude descriptive travel blog from the middle of it. No matter what, I wanted to get it out there, only because, not many people have had the experience as such, even though all of it happened right inside Bangladesh. So here it is, an incoherent mixture of prose and poetry…

Sarah-Jane Saltmarsh wrote

The road was long and it wound and it wound

The sun beat down and the leaves reached out to stroke our faces

The breeze flirted but wouldn’t commit

We melted like kulfi without ice.

Green uniforms stopped us

Orange and green uniforms stopped us

The breeze continued to elude us.

We wrestled with forms

Filled out earlier

Details

Which had already been sent

Calls

Which had been made.

We stopped

And started

And waited

And yelled

And melted on the side of the road.

And finally,

It was deemed safe enough for us to enter Rangamati

Likely the safest place in the country.

We checked in at the Parjatan Hotel

An embodiment of the government in architecture

Strong, functional, slow and rigid.

The view took our breath away

The water was stunning blue and went on forever, and glistened like a million wedding saris

We took a second to sit in the grass and play with the lojjaboti.

The pineapples sold at the edge of the lake tasted like sunshine.

They were sold by men with large smiles and small hips, and colourful gamchas wrapped around their heads. They sat in red and blue boats, on spiky green pineapple-mountains, yelling at passersby.

After waiting for our mandatory police escorts for so long that we were no longer hungry, we set off across the water to Peda Ting Ting, a tiny restaurant on a tiny island. We were accompanied by three armed policemen, all of whom were obviously hungry also—for anything to break up their peaceful day. The breeze relented and finally settled in for some quality time with us.

Slow food. We ordered and then went to explore. The island was green and lush.

The food was a feast, encased in bamboo and steaming with flavour

We’d never be able to finish it – but somehow it all, and smiled for the rest of the day

It was the best food I’ve had in Bangladesh.

Back on the shore

Or on one of the shores

What is island and what is mainland is not simple in the vastness of Kaptai Lake

We climbed down the steep edges of the island and dipped our toes in the water

The waves was clear, the sand white and the sun bright.

We drove along a tiny road separating two islands

The sky was on fire

We drove through a pink and red ocean

The colours seemed to rage, just for us, for hours

Sunset in the seas are often celebrated, but sunsets in the hills are the real secrets.

We went to our friend’s house who was getting married.

There were mountains of sweets, piles of beautiful handwoven clothing and giggling young girls holding hands in every corner.

We wandered in awe through the long tunnels of fairy lights which would guide the bride and groom to the guests the next night.

The wedding started at Sabarang Restaurant

It was small and warm, with a lot of love and a lot of photos

We stood on the lawn in our shiny outfits in the afternoon sun holding flowers.

Then the bride left her parents’ house.

Tears fell.

I continued writing

After a few hours, the night quietly crept in, and it was time to head to the groom’s house. We piled into cars and buses, ready for the evening rituals. Monks chanted life advice—serene, timeless words—and the wedding ceremonies began.

The next day started with a walk across the famous hanging bridge. Sarah-Jane couldn’t resist playing with the quirky exercise equipment at the nearby park on the hill. We wandered around the water, enjoying the peaceful vibe, until we met an enthusiastic boy who insisted on taking us into his village. Intrigued, we followed him.

At the uphill entrance to the village, we stumbled upon a tiny tea stall. The tea, blended with fresh cow milk and paired with local bananas, was heavenly. On our way, we passed a primary school. The bright, curious eyes of the children lit up our morning.

As we ventured deeper, we spotted a bamboo temple perched atop a hill. The view was spectacular—Kaptai Lake stretched endlessly below, shimmering in the sun.

Our village adventure took an odd turn when the police called the boy’s cellphone, demanding we return immediately. How did they even know where we were, let alone his number? The boy was terrified. We rushed back, hearts pounding, unsure of what rules we might have broken, angry and annoyed at the same time.

We tried to find out and confront the people behind this disturbance and went up to the nearby police garrison. We found off-duty officers lounging in lungis, clueless about the mysterious phone call. We voiced our frustrations: if there are rules, they should be clearly communicated. And why scold the boy? If anyone broke the rules, it was us, not him!

Later in the afternoon, we went to see the Chakma Rajbari.

On the way, we couldn’t resist detouring to the preparations for the Kothin Chibor Daan Festival on the other side of the river. A free ferry, sponsored by the king, carried us across. We crossed. We wandered around the festival venue getting ready for the big event.

We were lucky to have been able to catch a glimpse of the preparation, there a lot of young men and women were making paper flowers and origami style decorations. A few men were also working on preparing the grounds for the weaving competition.

We continued to explore the Rajbon Vihara, the central monastery of his holiness Bono Bhante. serenity enveloped us. The place was spotless, with a sense of sacred calm. Puppies frolicked with their mother, melting our hearts. We vowed to return for the main event the next day.

Came back to the ghat, crossed the river to visit the Rajbari this time. Avoiding the typical public plazas in the compound, we sneaked into a big garden with beautiful trees with a tiny little hut overlooking the river and green a far. It was the entry to the residence of the king. There was a sign “no trespassing” we saw it, we couldn’t resist wandering in. With a little hesitation, we wandered around the garden. We laid down on the grass, probably took a little nap. The soft sunlight of the afternoon filtered through the foliages, the breeze, and the soft layer of grass beneath… An old man walking around, we thought, we got caught, and he will kick us out. The way he walked as if there is no other being or object is around the earth, he did not even looked at us.

Later, we found an alley where tribal women sold stunning fabrics—ridiculously cheap and undeniably beautiful. The sunset painted the sky as we waited for the ferry. Birds flew homeward, casting silhouettes over the tranquil river.

We went to one of the popular restaurants at the DC Bungalow complex, for dinner, or the first meal of the day. It was a weird restaurant. But with surprisingly food was good—or maybe we were just starving.

We sneaked out of the wedding to the nearby District Commissioner’s office to sort our travel permissions for Bandarban, only to learn that each district in the Chittagong Hill Tracts requires separate permits to enter. Disheartened, we gave up on Bandarban. We lost a good amount of money that we paid in advance for this fancy resort in Bandarban, that was our only planned splurge on this trip.

Back at Parjatan, we were greeted by a sign warning about monkeys. Laughing it off, we left the balcony door open—until a vicious monkey attacked! It tried to storm into our room, leaving us both terrified and bewildered.

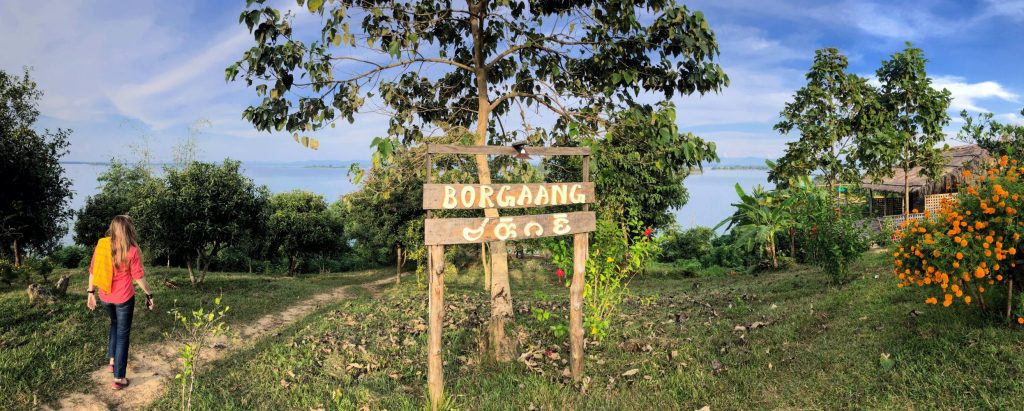

We started the long journey to Kaptai. On the way we stopped at Borgaang, a picturesquely beautiful cottage, restaurant with a little kayaking facility! Next to it there is another restaurant, Beranyya Lake Cafe. We ate there. We immediately decided to ditch Parjatan and stay here, once we get back from Kaptai.

The landscape around the journey to Kaptai was a symphony of water and hills! We stopped our three wheeler a few times to reduce the sin of quickly skipping the stunning horizons on both sides. It was water and greens hugging each other in the hilly terrain.

We looked like burning red dots in the middle of all the greens, chirpy, like a fireball of happiness.

The boat ride at Kaptai was a bit underwhelming. It was big, a bit messy. The barrage was a constant reminder of the whole daunting history of the creation of this massive lake that ate all the indigenous villages and communities. We didn’t go very far. We rather stopped at this massive pile of bamboo in the river. Jumped around.

We rushed back to the city in the dark.

Next morning, we packed our bags from Parjatan. Straight went to Borgaang, settled in our little hut overlooking the lake in the middle of a little jungle. Borgaang is spectacular, they have beautiful gardens, a bamboo made conference hall and lovely small huts. Although, part of being in nature is embracing all its elements as well, that included two massive spiders that were crawling around the room and the bathroom, while the whole facility is off the grid with periodic electricity only to light a tiny bulb and one socket for charging our phones for a few hours after the dark.

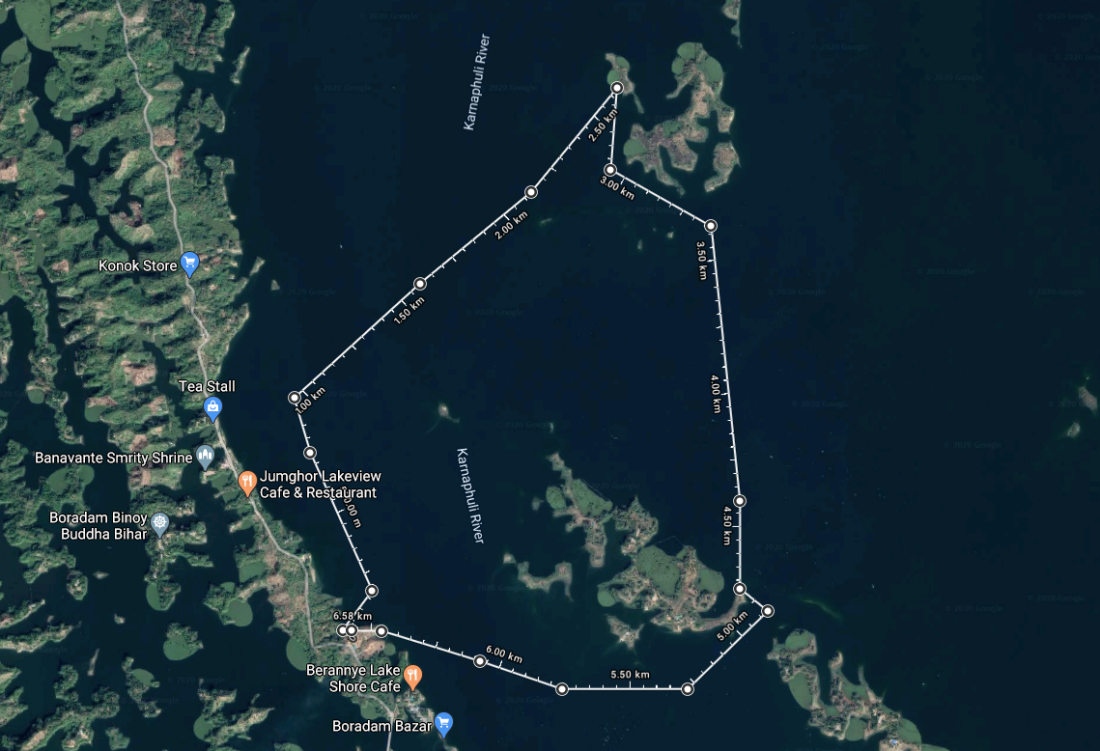

We did not care much about the rooms while all we wanted to do was to stay away from any confinement of walls. We jumped into kayaking towards the infinity of Kaptai lake. Leaving Borgaang, we aimed at the submerged former house and the birth place of his holiness Bana Bhante, which is nothing but a colourful minaret in the middle of the water now, surrounded by flags. After reaching near the Bana Bhante house in the water, we were manoeuvring the kayak to start rowing towards the vast water of the north-east, while we were at it, Sarah dropped her Samsung Galaxy Edge in the water. She quickly jumped into the water to find it, nothing, the phone quickly went down the deep water. We somewhat agreed the specimen of the cutting edge technology is a sacrifice to Bono Bhante’s philosophy of living with nothing. Sarah suddenly without a phone was completely disconnected from her friends and work.

We kept rowing west, far away from the side of Borgaang, about 2.5 kilometres north we reached this secluded island in the middle of nowhere. We stopped, tied the kayak, and walked up to explore the island. There was only one house in the entire island occupied by a family. They were not very comfortable or welcoming though, so we quickly left and headed back to the water. I was wondering while walking back, what if we found out that our kayak is missing! The tether might have given in.

It was still there, we started rowing, this time back to Borgaang. We were about straight 3 kilometres away, but locating the shore of Borgaang was difficult from there with the naked eye, as all you can see is a green horizon, there is no way to distinguish any place or landmark. We kept rowing based on assumption. Sarah was confident we could find the place. I was a bit hesitant. I kept checking the GPS, typical of me. By this time we were tired, we rowed like 4 kilometres in total already. We were floating around the vast water under the sun without rowing much for a while. The kayak was swaying and moving on its own in a gentle rhythm. Silent. Windy. There was only the sound of the wind and the water, and nothing else in the vicinity.

The target place we were heading towards turned out to be not Borgaang, and it is rather another island camouflaging in the horizon obscuring Borgaang behind it. After a bit of manoeuvring we had to go around the island. After about two and a half hours, and around 7 kilometres of rowing, we are back.

We sat down with the locals right outside Borgaang across the street in a tea stall. The whole social dynamic among the Chakma people of this village are so different from Bengalis in the town. The women are in charge in general, they are visibly taking the lead in every work and conversation.

That evening we were supposed to go to the biggest Buddhist festival of the year, the Kothin Chibor Daan at the Rajbon Vihara. The whole village near Borgaang was gradually getting empty, as everybody was heading to the festival. We somehow managed to find a three-wheeler after some phone calls.

Kothin Chibor Daan is a yearly festival where all the Chakma villages including a few other tribes like Marma, Tanchanghya and Tripura, more than four hundred they say, from all the districts of the Hill Tracts send their teams of best weavers to weave the orange clothes that the monks wear for the rest of the year. It is a activity starts with making of the cotton thread, followed by dying and drying, and finally weaving the fabric—all done within a 24 hours of span, it is a kind of labour intensive sacrifice and gifts from the villagers to the servants of Buddha, the monks and their young apprentices. All that they wear throughout the year are the four pieces of clothes that are made by the weavers from hundreds of villages in a day at the Kothin Chibor Daan festival.

We entered the festival through the street side from the south instead of the river this time, the area was densely packed, and dotted with permanent and makeshift shops and food stalls. We explored some of those shops full of local fabrics and handicrafts, incredibly colourful with intricate details. The road irrupts into a massive open space with a big stage (the festival stage of Rajbon Vihara) on one side. Every step of the place was fully packed with people watching an ongoing performance.

We kept walking to explore the weaving competition, the main ritual of the festival. The first step to weaving is preparing the threads itself from scratch. Making the cotton thread starts in the morning, and then dying and drying, all happens right here. The dying and drying take place on the same evening as the weaving. Piles of white cotton threads are dipped in the monk-orange colour dye, then they are wrapped around two bamboo poles, four persons hold each side of the poles to move and shake it on a wood burning flame to dry them, it is quite a manoeuvre and team work. I was sneaking into the groups with cameras without disturbing the process much.

We moved to the big pavilion where all the competing villages have a little space designated by a bamboo made boundary. Only about four to six people can sit in each of the stalls. Selected and designated teams of all female weavers from each village gathered from more than three hundred indigenous villages from across the Chittagong Hill Tracts—each team of the villages occupied one of the stalls there. Weaving, or waiting for their dyed and dried cottons to arrive. While they wait, they keep chatting, singing and paring their looms and spin wheels, no electric machinery, it’s all rudimentary makeshift weaving tools. They all look so happy! They will continue to weave throughout the night, and offer the fabric to the monastery by the morning.

Compared to other festivals of Bangladesh of this scale, Kothin Chibor Daan seemed much less chaotic, people are not shouting at each other for work, allocation the places or access. The gender balance was unprecedented with women leading the show almost everywhere. Everything is densely packed, so much going on, yet people are respectful to each other, while everyone is probably focused towards one big goal, making their village do better, and win the competition of making the best fabric for the monks tonight. The core purpose remains set, that is to offer something to the monks—which turns everything of this festival into a prayer or offering to his holiness Bono Bhante and his monk disciples.

On the way back, we stopped by the festival stage, where a musical drama was being performed. It looked like quite a modest arrangement, yet everyone seemed to be watching it as if they were transfixed. As far as I could decipher, part of it was mixed with dialogues, music and dance that sounded like a mixture of Bengali, Sanskrit and Chakma language.

We took a different route and exited through the main entrance of Bono Vihara. Every single inch of the place was dotted with people. There were numerous big boats across all sides of the water around Bono Vihara complex. Many of them had lights on, and people were going in and out frequently, we were wondering what was going on there. It turns out, most of these boats are floating restaurants. They come from different parts of the region during the festival to join in, enjoy, sell and serve.

It was pretty late already, we were a bit worried about finding a ride back to Borgaang, since that is a bit of an out of the way place in the middle of nowhere in between Rangamati town and Kaptai, where probably not every other auto-rickshaw would want to go at this hour in the night. And as anticipated, a few that we asked did not want to go.

Russel, the little angel from Borgaang, suddenly appeared in the crowd, as if he heard us. He is neither good at Bengali nor English, but what he said hesitantly was, he does not want to go home as a lot will be happening in the festival throughout the night which he does not want to miss, and once he goes back to drop us off, he probably won’t have a ride back. He was so shy and apologetic about it, we laughed and said that he doesn’t have to go with us, all that he can help with is finding a ride for us, and he did that in a blink!

Next morning, we went out to explore the nearby area of Borgaang to check if we can find a trail up or down the hill and water to hike. Everything around the palace is stunning, yet walking into any unknown forest or hill without any locals accompanying us can be a bit dangerous. And as usual, of course, we jumped into doing just that. It was a tiny hill down the forest to the lake, yet the steep slope and almost uncharted trail became a bit challenging to climb back.

After coming back in one piece, we had a lovely breakfast at Borgaang’s restaurant with an out-worldly view. We said goodbye to our little hut, named Sangrai, stared at the vast water of the mix of Karnaphuli river and Kaptai lake before hopping on to a tuktuk back to Chittagong.

In Chittagong, while we still had some time before going to the airport, we decided to check out the famous original Batighar book shop. What a lovely treasure trove of knowledge in a little place in the middle of the city! As we headed to the airport, Rangamati’s magic lingered in our hearts. How had we not known about this slice of heaven before?

Most of these photos (only) are released as Open-source under Creative Commons BY-NC 2.0 License, free to copy, download for non-commercial use from this Flickr album.