The water and their surroundings in Banani and Gulshan lakes are a curious indicator of these neighbourhoods in Dhaka. Don’t be deceived by the photo with the reflection on the water; that water is often visibly black, filthy, smelly with sludge building on top, probably nothing survives in there other than bacteria and mutant fish. Various drainage and dumps are directly connected to the lake, all coming from the richest and fanciest facilities around.

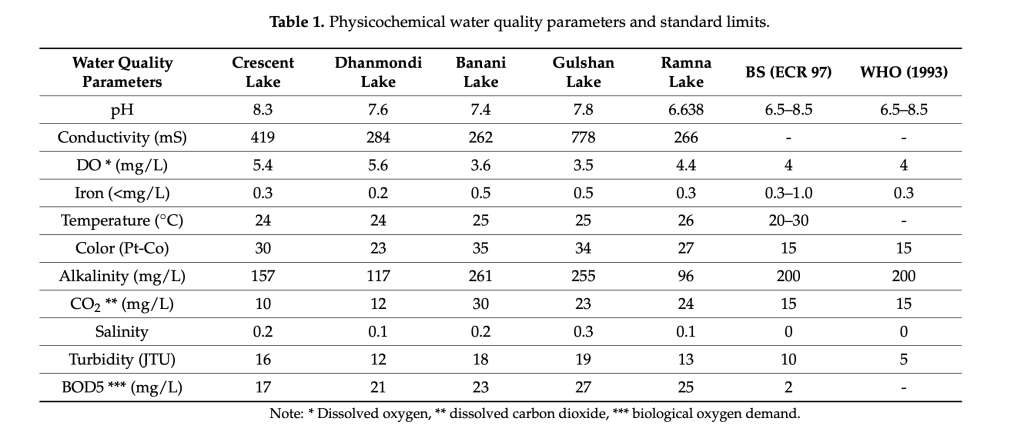

If we like to dig deeper and quantify the quality of water, this recent study should be helpful. It shows the comparison among some of the key parameters of water quality extracted from samples from five water bodies in and around Dhaka city. The study is done recently in May 2024 by a group of researchers (Bilal, Iqbal, Li, and Tulcan) from two universities in Beijing and the International Water Management Institute, available on the Research Gate.

Among various parameters in the numbers, the last line item BOD5 (Biological Oxygen Demand) is an important indicator of biological pollution. It indicates the amount of dissolved oxygen consumed by microorganisms while decomposing organic matter, the expected normal is 2 mg/L as specified by Bangladesh Environmental Conservation Rules of 1997 (BS ECR 97), whereas Gulshan Lake contains 27 mg/L of BOD5—that’s 13 times more than normal! The amount of CO2 is also a crucial indicator of life in water, the less is better. The 15 mg/L of CO2 is the maximum limit set by WHO and BS ECR, where Dhanmondi Lake shows 12, ok, but still pretty bad, Banani Lake logs a hopping 30 mg/L.

Then surprisingly, the heavily guarded entire sidewalks of Banani lake from Mahakhali to Gulshan Society Mosque are often occupied by thugs. There is everything there, from ganja, drugs to prostitutes right behind the most expensive properties in town. That too is guarded by police round the clock from each ends of the lake, for example, there is a police check point at Kamal Ataturk Avenue on the Banani lake bridge, on the other side there is another check post near Gulshan Society Mosque. This patch of the lake’s eastern sidewalk (entry from the opposite to Payala cafe) goes completely dark after evening, and all sorts of wrong thing can be found throughout the walkway, carefully “guarded” by the police on both sides.

Notice that I wrote “right behind the most expensive properties in town”—focus on the “right behind,” it has been long since we have turned our back at water. Water is now generally left behind the buildings, the buildings and roads do not face the water anymore like it used to do, when we used to arrive at a place through the waterways. Roads do not end at water, they cross it or bypass it. Buildings do not face the water anymore, water is in the dirty backyard. As the water is now physically, structurally “behind” us, we tend to be less respectful to it.

Our behaviour and attitude towards water contribute to its wellbeing. This so-called “tristate” area is where country’s richest people live, and places that attract foreign immigrants and diplomats. The third group that live here kind of feel out of place, and constantly wonder why they are here. All three of these groups have some direct and indirect contributions that result in the colour and smell of the water.

Much like the entire Bangladesh, Dhaka is surrounded and criss-crossed by rivers. The lakes we see nowadays, Hatirjhil, Begunbari, Dhanmondi, Banani, Gulshan lakes, were all connected to each other, and also to the rivers that surround Dhaka. They have turned into lakes because we shut them down. They were not supposed to be lakes to be begin with.

Similar to what happened in Bangkok, many of the original canals got occupied, filled up, divided, disconnected and turned into stagnant lakes. Recently, there are some initiatives in Bangkok to reconnect all the old water bodies of the city to the rivers, and bringing back their original flow, so that there is no stagnant water anywhere. Dhaka is nowhere near that of course, as nobody is thinking much about the water. However, it is a much needed thought and overdue initiative that could fix many a problems with the quality of water, mosquito and also traffic! All these waterbodies could be turned into a big network of water transport system connected end to end from Turag to Balu, Buriganga to Gulshan, and to the rivers in the north.

Back to the hoods, the first group, the richest ones who owns majority of the properties in the “tristate” do not consider themselves belonging to the neighbourhoods. The owners themselves moved here from older neighbourhoods of Dhaka, they dwell in that reminiscence and nostalgia. The second and third generation probably grew up here but they do not want to live here. They are mostly based in the North America, Europe or Australia, or want to move as soon as they can. Big part of their conversations occupy the stories from outside of Bangladesh. They ‘visit’ Dhaka, they don’t live in. They ‘stay’ in their houses, they don’t connect with the neighbourhood or the people. They slide themselves from one door of air conditioned cocoon to the next, quickly escaping from the air, elements and human species, as if the neighbourhood atmosphere is something that is going to kill them. They never walk. They do not belong. They do not care.

Hence, nobody owns the sidewalks and lake-side walkways in Gulshan, Banani and Baridhara. They are just there, like orphans—used by people who do not live here, probably coming for work, or passing through the areas. This group as well do not belong or take the ownership, they can not; they also do not have the power or means even if they want to.

The third group who live here but feel a discontent disconnection, are a group of upper middle class people who rent apartments in the hoods mostly for the sake of the proximity to their work places and other conveniences. They feel misplaced, and suffer from an imposter syndrome. They want to help and contribute to the betterment of the walkways and water, they don’t have the ownership or authority to do anything.

Comparing this case with Dhanmondi, there the residents and property owners who live there for generations actually go out to walk by the lake, that’s why the walkways there are walkable. They are owned, maintained, loved and taken care of. Even the younger generations of Dhanmondi are a little different, they belong in the neighbourhood regardless of their lifestyle, education, and access to bidesh. I still see local youngsters sit and hangout on the sidewalks, lakes, intersections, play-fields.

That’s why the water in Dhanmondi lake is much cleaner than Gulshan. It is owned, loved, respected and celebrated. In our region, we cannot afford to turn our back to water, we cannot afford to let it die, it will eventually bite us back, one way or the other.

Probably the best way to mitigate this is by taking the first step, literally, go out, and walk, talk the first step, claim the ownership. If the locals of these neighbourhoods would walk and occupy the sidewalks, enjoy the lakeside walkways, then everything would automatically start improving. Because, we will start to connect, touch, embrace, own and belong—that is the core to any improvement in and around the water quality, walkability and overall quality of life.